By Sarah Nason

When most animals grow up, they pretty much look the same. For instance, can you tell the difference between these two squirrels?

Besides the fact that the one below might have a mild obesity problem, I couldn’t tell you who was who, even though I know they’re two different individuals that I observed on two different hiking trips.

Some animals, however, like to break this mold: enter, the Wellington tree wētā.

It’s hard to believe, but both the individuals in that photo are mature adult males of the same species Hemideina crassidens: the one on the left just weighs about twice as much. Informally known as the Wellington tree wētā, this is a giant species of cricket that hails from New Zealand and has many other equally juicy-looking relatives. This phenomenon in which a species can exhibit more than one final form/appearance is called polymorphism and is abundant in nature. Colour polymorphisms are probably the best-known type of polymorphism, such as the light and dark morphs of jaguar:

Once considered a different species, the black jaguar is now recognized as a different morph of the same species Panthera onca. It also happens to really evoke that “evil twin” archetype.

The polymorphism in Wellington tree weta is not quite as striking as that of our fine-looking jaguar friends, being a size polymorphism: individuals grow up to achieve distinctly different final body sizes. The polymorphism of the Wellington tree weta is unusual for a couple of reasons: 1) only males have multiple forms (females are all roughly the same size), and 2) there are three different potential forms. Both of these facts beg the question: but why?

Enter, a second character that will try to answer these questions: the grad student. This is how I spend most of my days as a Master’s student at UQÀM, trying to sort out the mysteries of diversity that Mother Nature puts forth. (I mean, that actually makes my work sound pretty impressive; in reality, I spend most of my time making tiny salads for the wētā that we have in our lab.)

A beautiful selection of personalized salads for our pampered colony of wētā held at UQÀM.

But when I’m not doing kitchen work for my insect overlords, I’m trying to figure out how evolutionary theory could explain those two key observations. Largely because I’m just curious, but also because polymorphisms represent a form of biodiversity that we would like to conserve, and in order to manage and conserve it we first need to understand how it works.

Why do only the males get to have different outfits?

Previous work by other scientists has mostly gotten to the bottom of this question – in fact, when animals display size polymorphism, it’s often only expressed in males. We think this happens because of how intensely males compete amongst themselves to acquire matings to females. That might seem unrelated, but a little crash course in sexual conflict theory can make sense of it: females have to invest time in gestating and laying eggs, making them more interested in producing a smaller amount of high quality offspring. In the meantime, males have no incentive to be picky and benefit the most from just mating a lot and producing the most offspring possible. As a result, males compete intensely amongst themselves to mate with a limited number of females. This generates pressure to develop alternative strategies for acquiring matings: basically, when the marketplace is this competitive, you’ve gotta start getting creative. Smaller male morphs are probably optimized to employ different strategies to get with the ladies compared to larger male morphs: for example, small males may be “sneakers.” Yup, there’s a word you never wanted to hear associated with sex.

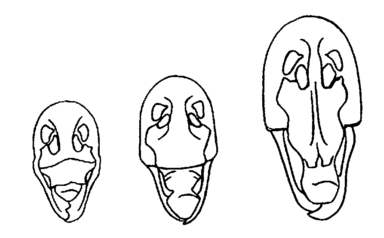

Illustrations of the three different male head sizes observed in the Wellington tree wētā (from Kelly & Adams, 2010). These drawings are only made better by the fact that they look like they have super expressive eyebrows.

“Sneaking” unfortunately means exactly what you think it does: small males, with their inconspicuous bodies and high maneuverability, dash in and mate quickly with females that are being guarded by larger males while the alpha’s back is turned. Animals are devious, and this is not just a weird wētā thing: it’s been documented in several species of fish and birds as well as other insects. So this gives us an idea of why only males exhibit alternative forms, although we haven’t yet confirmed that the smaller male weta use these ethically dubious strategies.

Salt, pepper, and…cumin?

Bringing us to the second question: why are there three different morphs? It’s common enough to see two alternative strategies: a dominant “guarding” type and a smaller “sneaker” type. So what is the middle-sized guy doing? Does he think that by being as bland and inoffensive as possible, he can sail through the dating world on a wave of average-ness?

The truth is that this remains a bit of a mystery to us. One theory is that when competition is especially strong for females, there is “room” for a further third strategy: the marketplace demands even more creativity in order to get an edge on the competition. The problem is, we’re just not sure what that third strategy is. Maybe it involves a mix of the two other strategies: Mr. Average might actually be a jack of all trades who guards females when he can, and when it’s not worth it to fight a male larger than himself, attempts to sneak instead. Fingers crossed, I will get closer to the answer by the end of my Master’s degree!

Want to learn more about the lives of these bizarre insects? Check out the NZ Department of Conservation’s page. Or just want to see more gruesome photos? National Geographic has a photo tag where you can explore amazing wētā photography.

Image Credits: Wikipedia, Kelly & Adams, 2010, Sarah Nason.

This post was adapted from an original post at sarahnason.wordpress.com.

0 Comments