By Michael Paulauskas, a MSc graduate from Concordia University

For starters, I’d like to apologize for the seemingly sensational title. No, I won’t be writing about actual hauntings, ghosts, or any other supernatural phenomena. Quite the opposite, I’ll be sharing with you my experiences with something relatively more mundane: urban soils!

It isn’t every day an ecologist brings up urban soils. Understandably, since urban soils are niche within already niche disciplines, that is, soil sciences and urban ecology. The former tends to concern itself with soil properties relating to nitrification and irrigation, naturally, as these pertain most directly to crop growth and conventional farming. The latter tends to concern itself with political and sociological aspects, but in the case of ecology, its interests often lie with urban greenspaces and the charismatic species that live therein… in other words, trees and birds. So, urban soils?? Are there even soils in urban areas? True, I’ll concede that our mental images of cities are defined by vast stretches of built environments of asphalt and concrete. And, given this heavily impervious surface cover, city soils must surely be contaminated and degraded from our intensive urbanized land uses. Again, I concede that there is some truth to this. However, that did not stop me from studying land uses in Montreal throughout my MSc. Let me cut straight to the punchline: our land uses of today are tomorrow’s legacy.

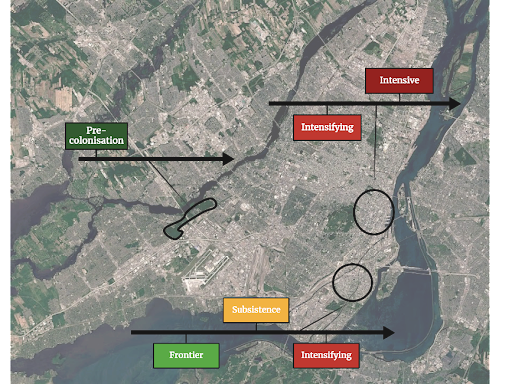

You see, cities are ideal candidates to study legacy effects of land uses. It is no surprise that our land uses can physically and chemically alter soils depending upon the type of land use and the intensity of that land use. A city’s development isn’t instantaneous but rather sequential; as the saying goes, “Rome was not built in a day”. What we see, then, are multiple co-occurring trajectories that create a heterogenous landscape. Some parts of a city could have historically been used for agriculture, but were later converted into residential areas. Other parts of a city could have historically maintained an unchanged and minimally disturbed land cover prior to the arrival of colonials, i.e., forested areas. In essence, a cityscape is a complex socio-ecological mosaic rich in historical land uses. Since ecological and pedological soil functions are inherently slow (it can take hundreds of years for one centimeter of soil to form!), then any persistent temporal variations incurred by historical land uses have the potential to affect our soils today. And therein lies my earlier punchline and the raison d’être for me wandering into the very niche world of urban soil ecology. By acknowledging the impacts that our past land uses can have on the land and the life the land harbours, we will be better equipped in future, particularly if urban centers are projected to expand with growing populations.

However, this isn’t my defense, so I do not have to convince you of the implications of my research. Instead, let me share with you two fun historical facts that my colleague Bella and I unearthed (pun intended) whilst trying to determine what the historical land-uses of Montreal were. Firstly, Montreal was once the largest producer and exporter of raw rock and stone in North America in the 20th century. This makes sense very quickly considering the sheer number and volume of quarries that littered the island back then. For example, and most famously, Parc Frédéric-Back used to be the Carrière Miron, a monstrous 70m-deep open quarry in the 1960s that was later used as the de facto dumping grounds for all collected municipal waste across the City of Montreal until 1988. Secondly, Mount Royal used to be known as Mont Chauve! In the early 1950s, the City decided to completely raze two-thirds of the trees at the summit of Mount Royal. I am leaving the *why* of this expressively vague because I want you to discover the – arguably disgusting – history behind the Morality Cuts. You can learn more about Montreal’s mindset post- World War II in a fantastic journal article here by a graduate student from the history department of Université de Montréal. The consequences of this huge loss of forest cover atop Montreal’s namesake was immediately felt. Massive dust clouds were generated and flew off into the city due to wind erosion. In the following years, the City decided to replant the summit with trees in hopes of recovering its surface. I suppose they learned their lesson!

About the author: Michael is a recent Master’s graduate of the Ziter Urban Landscape Ecology (ZULE) research group from Concordia University. His love for soils bloomed during his undergraduate studies where he was introduced to agricultural sciences. Now, he proudly dons the colloquial titles of Dirt Boy or Soil Guy.

0 Comments