Marian MacNair hears the trees fall in the forest

All over the island of Montreal this winter, municipalities have quietly been cutting down their ash trees.

It is a quiet tragedy occurring all over eastern North America. The numbers are staggering: there are around seven billion ash trees on the continent. Ash accounts for at least a quarter of the tree canopy in many urban areas. All ash trees in an infected area can be dead within five years. Come spring, they can all be gone.

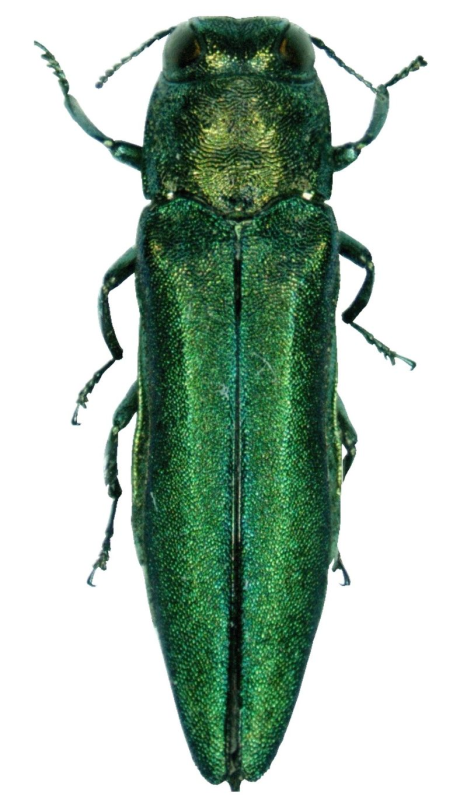

The die-off is caused by the emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis), an Asian beetle that arrived in the early 1990s and is decimating ash tree populations across the continent. A Google search documents the dying of hope: in the first decade, articles exhort areas to keep out the borer, or proffer plans to isolate or inoculate trees with insecticide. Now, city after region after municipality are announcing how they are going to get rid of their ash trees.

I think we can conclude that if an ash tree falls in the forest, scarcely anyone hears it anymore. But I would like to make a sound and appreciate the ash tree.

The ash tree is in the same family as the olive. Versions of the name can be found in most European languages, which means it probably dates back to the steppe horsemen who spoke the original of our languages. It always means spear, doubtless for the speartip shape of the leaves or the seeds.

The ash is a pioneer species. It was the first tree species to follow the glaciers’ retreat northward in America. Its fruit seeds (samara) have elongated wings, which allows them to get carried by the wind across distances farther than usual.

Despite the fact that the ash is not cold-hardy, populations can be found as far North as Hudson’s Bay, and are most likely remnants of a warmer world. In a triumph of determination over adversity, the ash, unlike cold-tolerant species, must rebuild its active cellular structures from scratch each year before it can leaf. Its freezing cells can burst and rip open the bark, leading to observable giant splits down the tree’s bark. It is one of the last species to leaf because it has to work harder than other tree species.

It is fast-growing but strong, preferred by woodworkers for its flexible, tough wood. It is used to make tool handles, lacrosse and hockey sticks, oars, bows, baseball bats, snowshoe frames, guitars, drums, veneers, chair backs, church pews, boat ribs, lobster traps, staircases, and basket ware, to name a few. There are/were many ash plantations in Europe and the U.S., and it was often planted on soil beds after strip mining.

It is adored by worms. If one goes out in the fall a week after the ash leaves have come down, they will find maple and oak and beech leaves, but the ash leaves will have already been pulled underground.

In an attempt to forestall the loss of all hope, scientists have been scrambling for solutions. They are experimenting with bringing in borer foes from their native habitats in Asia, such as a pathogenic fungus or a small parasitic wasp. But the cure could be worse than the disease: what else might these new foes impact?

Though many municipalities’ policy is to inoculate a few trees and cut the rest, not all ash succumb. The American Forest Service encourages people to report ‘lingering ash:’ trees which have survived 95% ash tree mortality. Only 60% of blue ash, a sub-species, die off. Ash is a champion stump-sprouter, so there will be saplings growing from 7 billion stumps. Like the elm, the borer won’t get them for a few years, so ash will join the ranks of the shrubbery. Whether it will die out completely will depend on whether it can set seed before the borer kills it.

But what do you do with 7 billion dead trees? Sadly, despite the wood’s many great qualities, most around here are being chipped or chopped into firewood, the final indignity. Some municipalities have done better, organizing to use the wood in various ways and holding seed-gathering parties.

In geologic terms, all this is just a blip on the biological timeline. It is hard to even imagine what the forest was like for the first explorers crossing over the Bering Strait to North America. The holes in the canopy will close, municipalities will plant new trees (hopefully more diverse), and most won’t even realize the ash is gone.

The trees fall in the forest. But they only make a sound if we hear them.

Sources:

- Dr J Fyles, McGill University

- Wikipedia

- CBC

- Trees in Canada

- Audubon Field Guide to North American Trees

- Spectator

- New York Times

- National Geographic

- Earther

- Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources

Marian MacNair grew up on a farm in the B.C. Interior before becoming a journalist and science educator in Montreal. A proposal to encourage urban gardeners to plant milkweed has resulted in a McGill Master’s project analyzing citizen science data for monarch butterfly habitat preferences for the Montreal Insectarium. Chasing butterflies means Marian doesn’t have as much time to maintain her blog. But you can still check out her views on spiders, Taiwan and her trashy cars at marianmacblog.com.

0 Comments