by Victoria Reed

In January this year, I packed up my things and jumped on a plane to Panama City. For the four weeks that followed, I traveled with about 15 other graduate students from McGill University, University of Illinois, and INDICASAT (A Panamanian University) around the entire country of Panama. The course we were taking, Tropical Biology and Conservation, brought us up into the rainforest tree canopy in Fort Sherman, hiking in the jungle on Barro Colorado Island, mist netting in Gamboa, bush-whacking in the Chiriqui highlands of Fortuna, and snorkeling in Bocas del Toro. Almost every day we participated in discussions with Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) research fellows and staff scientists, and learned about the breadth of research being conducted in the isthmus of Panama.

Fort Sherman canopy crane

Tropical Biology and Conservation graduate students on Barro Colorado Island

Blue-crowned manakin in Gamboa

Fortuna, Chiriqui highlands

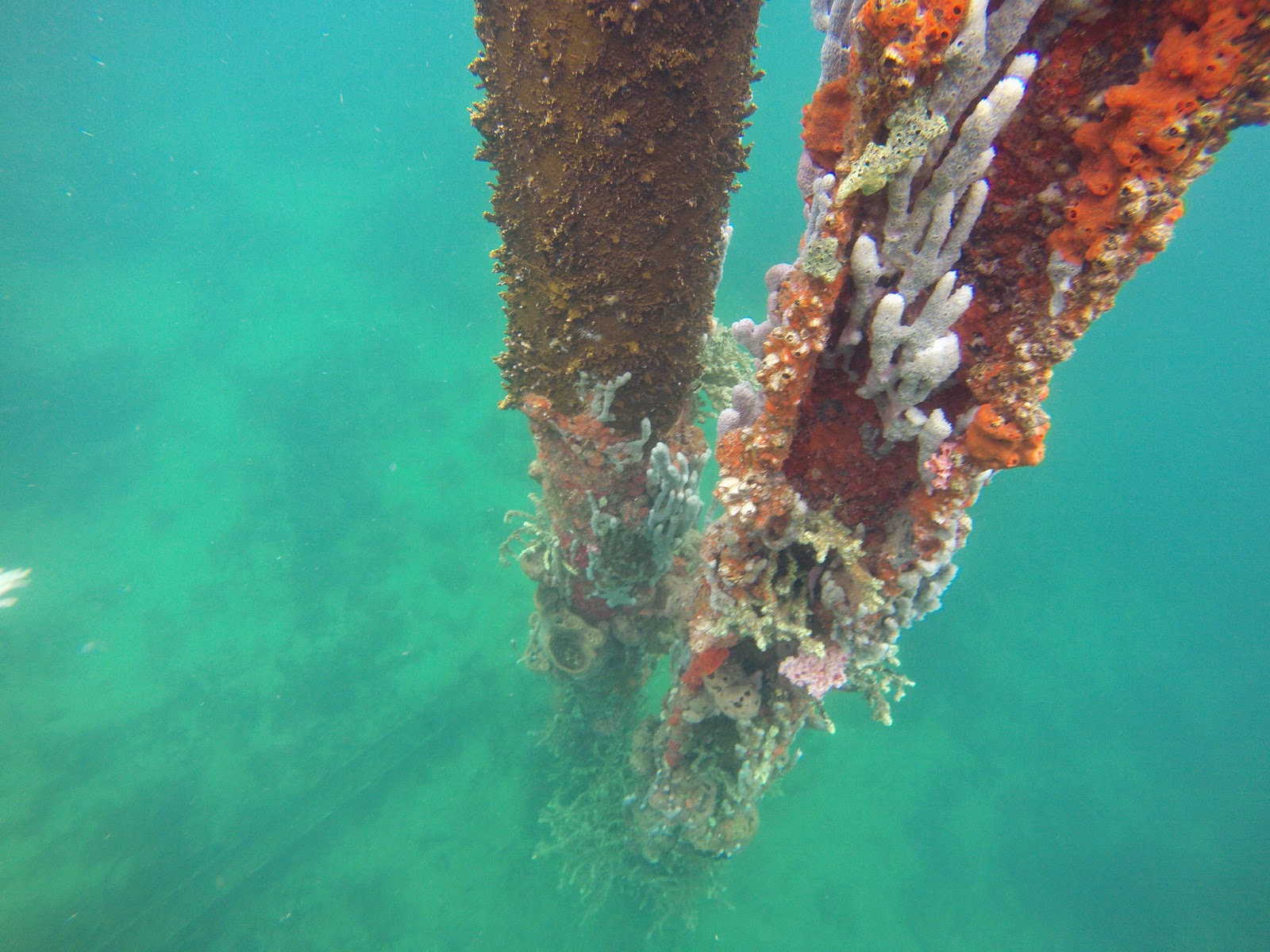

Snorkeling in Bocas del Toro

Apart from being an eye-opening experience to see so much of this beautiful and biodiversity-rich country, and to learn from world class scientists on all topics ranging from genomics, to conservation, taxonomy, community ecology and geology; as students, we also learned from each other. This course allowed us to form close ties with students from different disciplines whose paths might not have necessarily crossed otherwise. It was a humbling experience to gain appreciation for other realms of biology and geography that I have previously had little interaction with.

After this ~4 week course, I participated in another graduate course, entitled “Foundations of Environmental Policy”. This was an intensive one-week course that introduced students to the complex nature of environmental policy and the challenges of integrating science into a policy framework that must also consider the social, cultural and economic conditions of a particular system. This course, though only one-week in length, gave us a real appreciation for the hurdles that must be overcome to develop effective and publicly-supported policies.

Following these courses, I began working in Dr. Hector Guzman’s laboratory at STRI, who is my co-supervisor for my Master’s thesis, which is focused on ecosystem management practices and conservation. Specifically, my research will evaluate land use changes and hydropower development in the Changuinola River watershed in Bocas del Toro, Panama and provide baseline population distribution data of Trichechus manatus (West Indian manatees) in the Changuinola River lagoon system.

In the three and a half months that followed my graduate courses, I began developing a hydrological model for my study site and familiarizing myself with ArcGIS software, wrote grant applications, learned how to program and deploy aquatic temperature readers, depth finders, and submersible hydrophones, became adept at reading salinity levels using a refractometer and learned how to take turbidity measurements using a turbidity tube with a Secchi disk. My laboratory colleagues and I visited the Changuinola River, and spent just under a week taking samples, installing equipment and recording observations of manatee feeding marks.

The QCBS Excellence Award gave me the opportunity to go to Panama and learn so much about neo-tropical biology and research, begin my field and laboratory work for my Master’s thesis, and experience another culture and language quite different from my Canadian upbringing. A big thank you to the QCBS for making this experience possible!

P.S. If you would like to see more photos of the trips during the course, please see the following Flickr account hosted by all participants in the Tropical Biology and Conservation course, as this is where most of the photo credit lies (https://www.flickr.com/photos/igertneo/)

0 Comments