By Sarah Nason

This article was written based on the QCBS Intercultural Indigenous Workshop held at McGill University in November 2017.

Source: Onondaga Nation

This is the Two Row Wampum belt. It is the document that records a treaty of peaceful coexistence made in 1613 between the Haudenosaunee (or as settlers know them, the Iroquois) and Dutch colonists. The white stripes represent peace, respect and friendship; the purple stripes each represent the courses of two separate vessels traveling down the river of life together: a Haudenosaunee canoe and a Dutch ship. The paths of these vessels are parallel but never touch, representing the agreement that indigenous people and settlers should peacefully coexist but never try to steer the other group’s ship. The Two Row Wampum has come to be a symbol of the intended relationship between settlers and indigenous peoples for many whose history includes these same broken promises.

The reality is that settlers have not honoured their treaties with indigenous peoples. What was intended to be a history of respectful partnership is instead a history of oppression, discrimination and assimilation. Canada’s colonial history is marked by the abominations of residential schools, sterilization acts, Project Paperclip, and the ‘60s Scoop. Many in the room, myself included, had not known the full truth of this history. Suzanne Keeptwo, the facilitator of the Intercultural Indigenous Workshop organized by the QCBS in November 2017, brought such Indigenous realities to light with honesty and clarity. For those of you reading who are not familiar with the key events I highlighted, I encourage you to clink the links for context. Ms. Keeptwo told the story of the Two Row Wampum on the morning of the first day of the workshop, and it was with this in mind that we continued our discussions. Ms. Keeptwo is an educator, writer, editor and journalist of Métis heritage.

This two-day student-led initiative was spearheaded by QCBS researcher Marianne Falardeau and a team of six other graduate students: Gwyneth Anne MacMillan (UdeM), Justine Lacombe-Bergeron (UdeM), Allyson Menzies (McGill), Élise Morin (UdeM) and Cécile de Sérigny (UdeM). Over the course of the workshop researchers were informed about indigenous histories and realities in Canada and encouraged to consider these contexts when it comes to performing their research.

The 2017 Intercultural Indigenous Workshop organization committee.

On the evening of the first day, a discussion panel was held with particular attention to research in Canada’s North. In recent years researchers have become more and more conscious of conducting their work with the permission, involvement, and engagement of Northern and indigenous communities. While there is still much work to do, those that had some experience lent their voices to the panel along with representatives from indigenous communities. I offer here the key points and themes from the panel as a beginner’s toolbox for thinking about how best to collaborate with indigenous peoples and communities when conducting research:

Taking the time to build trust

Researchers from the Urban South (the urbanized population of Canada that is concentrated in the South) can be understandably negatively perceived when they arrive in the North, taking into context the harms that have been done (and the inequalities that persist today). Respect for communities means recognizing their autonomy and culture and not imposing urban Southerner values. Researchers need to show that they are genuinely committed to having the respectful relationship defined by the Two Row Wampum treaty and other indigenous norms and codes of conduct. As a gesture of basic respect, the purpose of the study and what it will entail should be made clear to the community from the outset.

Building trust takes time, but is arguably the most worthwhile pursuit to keep in mind. Researchers should plan extra time into their field seasons in order to include community collaborative work. It was especially recommended that researchers make the time to arrive early in communities before beginning their research in order to get to know the community. Panelist Nina Segalowitz recommended starting with something as simple as bringing a box of Timbits when you arrive. Show that you have good intentions and you want to listen.

Panelist Nina Segalowitz responding to questions during the panel on research in Northern communities.

Being conscious of generating an equal exchange

Respect for communities also means taking them into account as stakeholders in the research project and considering the impacts of the study on the community. Importantly, community members should be offered the opportunity to be part of the research process. This could take many forms, including but not limited to: consulting communities prior to beginning research, paying community members to help as field assistants, inviting community members to co-author papers, or co-writing grants together that will benefit both the researcher’s program and the community (an example from panelist Dr. Murray Humphries’ experience). Adjusting the project and its objectives to be of greater relevance or benefit to the community should be considered. Researchers were encouraged to think creatively about how communities can be involved, and most importantly: to ask communities how they would like to partake!

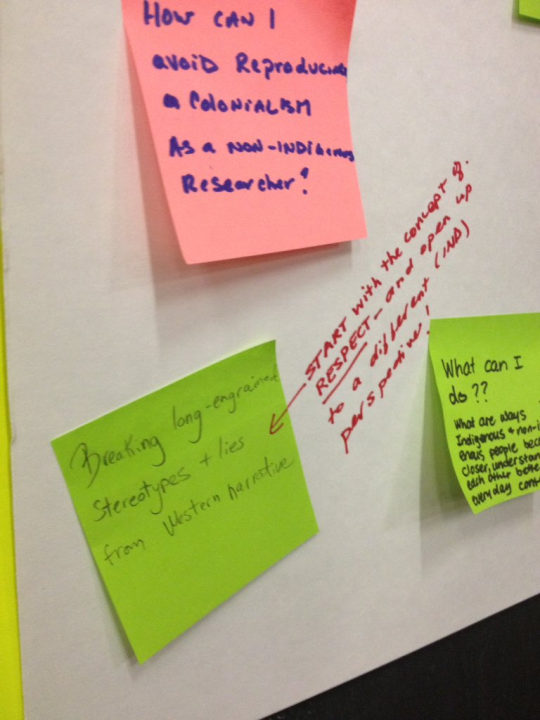

A board of sticky notes used to brainstorm ideas for improving relationships and collaboration.

Giving back to the community

Researchers should find meaningful ways to contribute to the community and avoid just arriving, taking data, and leaving. Panelists encouraged researchers to expand their contributions beyond the scope of just the research project: find ways to contribute to and participate helpfully in community events. If there is a need for volunteers in the community to achieve something outside the scope of the research, this is a worthwhile pursuit researchers should consider! It was also strongly emphasized that ensuring there is time and money to return to the community to share the results of the study is of crucial importance. It is understandably confusing (and potentially offensive) to have a newcomer live in your midst for several years of data collection, and then never hear why they were there or what they found.

QCBS students: interested in getting involved?

The QCBS would like to organize another edition of the workshop next year in Québec City. The committee would love to have new members and is looking to improve the diversity of the team; it would be particularly useful to have some people based in Québec. If you are interested in joining the Intercultural Indigenous Workshop committee, please contact Sophie Dufour-Beauséjour (sophie.dufour-beausejour[at]ete.inrs.ca). If you are interested in keeping up with the activities of the workshop, please join the Facebook group!

Étudiant.e.s CSBQ : voulez-vous vous impliquer dans cette initiative ?

Le CSBQ souhaite poursuivre l’aventure l’année prochaine et voudrait organiser une troisième édition, cette fois-ci à Québec. Le comité d’atelier serait ravi d’avoir de nouveaux membres au comité organisateur, et chercherait à augmenter la diversité dans le comité. Il serait particulièrement utile d’avoir des personnes basées à Québec. La personne-contact pour les intéressé.e.s est Sophie Dufour-Beauséjour (sophie.dufour-beausejour[at]ete.inrs.ca). Vous pouvez également vous joindre au groupe Facebook!

0 Comments